When a loved one passes away, the legal responsibilities that come next can feel overwhelming. Many Texas families find themselves trying to decipher complex probate terms while grieving, and two of the most common roles you'll encounter are executor and administrator. We understand this is a difficult time, and our goal is to provide clear, straightforward answers.

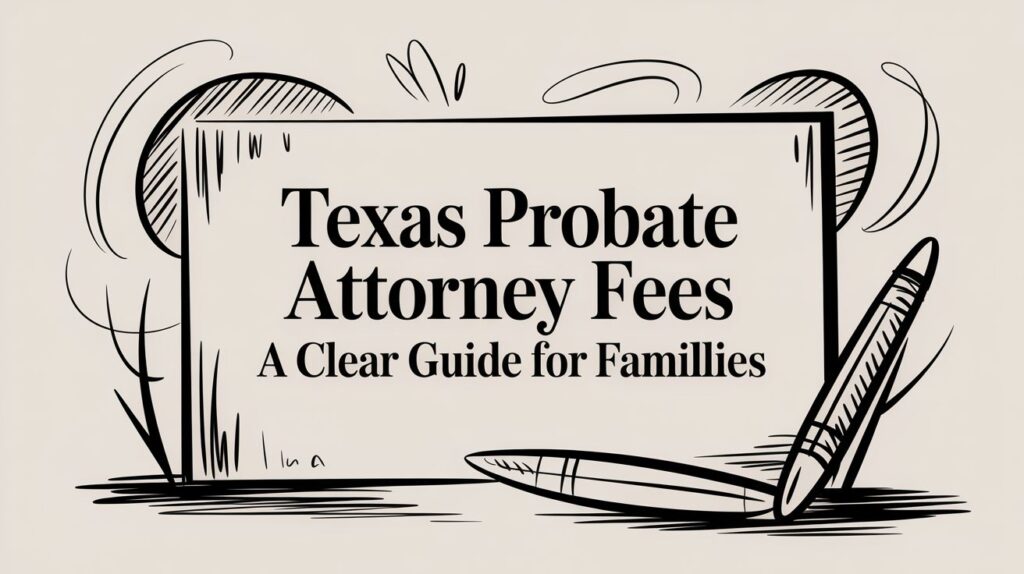

While both roles involve managing a deceased person's estate, their source of authority and the path they take through the probate system are worlds apart. It all comes down to one simple question: did your loved one leave a will?

Executor vs Administrator: An Overview for Texas Families

Losing someone is hard enough without having to navigate a legal maze. The easiest way to understand the difference between these two roles is to think about who made the choice.

An executor is the person your loved one trusted and personally selected in their will to carry out their final wishes. They were hand-picked for the job.

An administrator, on the other hand, is appointed by a probate court when someone dies "intestate"—or without a will. Since the deceased didn't name anyone, the court steps in and appoints someone based on a strict legal hierarchy defined in the Texas Estates Code. This isn't just a difference in title; it fundamentally changes how the entire estate is managed, often adding stress and uncertainty for the family.

Comparing the Roles

An executor’s authority flows directly from the will itself. This often allows for a much smoother and more private process in Texas called "independent administration." It means the executor can handle most of the estate’s business—paying bills, selling property, distributing assets—without having to constantly ask the court for permission, saving time and money.

In sharp contrast, an administrator's power is granted by the court and remains under its close supervision. This usually means a "dependent administration," which can be longer, more complicated, and more expensive, because nearly every major action requires a judge's sign-off.

This simple decision tree shows how that initial question—was there a will?—sets the entire process in motion.

As you can see, the will is the critical fork in the road. Its existence determines whether your family will work with an executor your loved one chose or need a court to appoint an administrator.

This distinction is a cornerstone of Texas estate law. The procedural step of appointing an administrator often adds a delay of 4-8 weeks before anyone gets the legal green light to act, while an executor's role is validated as soon as the will is probated. For a deeper dive into these timelines, you can find great insights from estate law professionals at scaringilaw.com.

Key Differences at a Glance

To make it even clearer, here's a simple, side-by-side look at how these roles stack up in a Texas probate case.

| Characteristic | Executor | Administrator |

|---|---|---|

| Source of Authority | Named in the deceased's will | Appointed by a probate court |

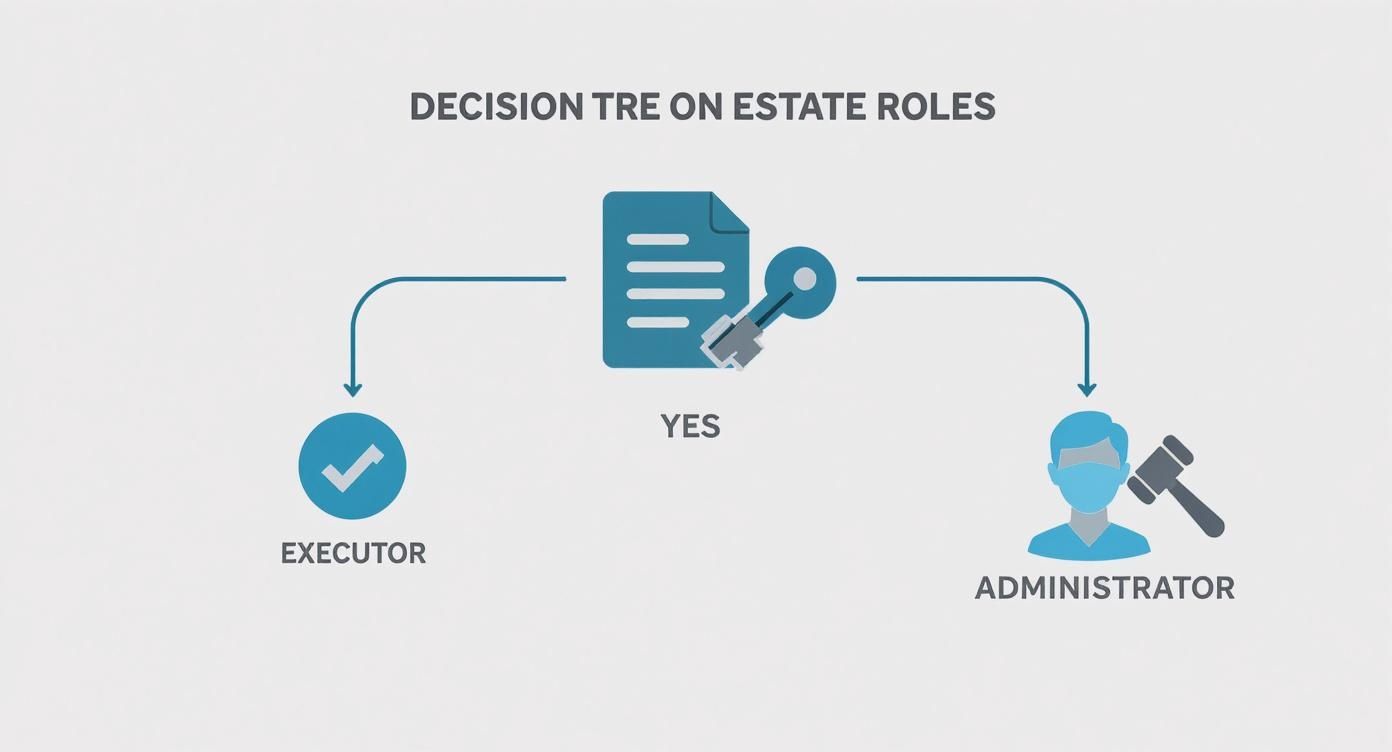

| Legal Document | Receives Letters Testamentary | Receives Letters of Administration |

| Guiding Document | Follows instructions in the will | Follows Texas intestacy laws (Texas Estates Code, Title 2) |

| Court Oversight | Often serves independently, with minimal oversight | Usually requires constant court supervision |

Ultimately, understanding whether you'll be dealing with an executor or an administrator gives you a clear picture of the road ahead—how much court involvement to expect, potential timelines, and the source of the rules for settling the estate.

The Executor's Path: How a Will Guides the Process

When a loved one leaves behind a valid will, they’re giving their family a tremendous gift: a clear roadmap for settling their affairs. This document is the starting point for the executor’s journey. The first step is to formally submit the will to the proper Texas court in a process known as filing for probate. This kicks off the legal process of validating the will and officially recognizing the executor’s authority to act.

The will is much more than a simple list of wishes—it's the source of an executor's power. By naming a specific person, the deceased has already told the court who they trust to carry out their instructions. This personal endorsement dramatically simplifies the initial court hearings, as the judge's main job is simply to confirm the will is valid and that the named executor is qualified to serve.

From Nominee to Appointed Fiduciary

After the will is filed and all required notices are sent out, the court will schedule a hearing. Here, the judge officially appoints the nominated executor and grants them a critical legal document known as Letters Testamentary. Think of these letters as the executor's official key to the entire estate.

With Letters Testamentary in hand, the executor can finally get to work. They now have the legal power to:

- Access the deceased’s bank accounts.

- Communicate with financial institutions, government agencies, and creditors.

- Gather and manage all estate assets, from real estate and vehicles to personal belongings.

- Settle the estate’s final debts and file necessary tax returns.

This single document is the tangible proof of their authority, empowering them to act on behalf of the estate. The path to getting these letters is fundamentally different from the one an administrator takes, a topic you can learn more about in our guide on the differences between Letters Testamentary vs. Letters of Administration.

The Advantage of an Independent Executor

Most well-drafted Texas wills contain a crucial provision appointing the executor as an “independent executor.” This specific language, allowed under Title 3 of the Texas Estates Code, is a game-changer. It permits the executor to handle the vast majority of the estate’s business—like selling property, paying creditors, and distributing assets—without having to ask for the court’s permission at every turn.

This independence dramatically cuts down on the time, cost, and headaches of the Texas Probate Process. It allows for a much more efficient administration, reflecting the deceased's ultimate trust in their chosen representative. Without this provision, the process would look more like a court-supervised dependent administration, erasing one of the biggest advantages of having a well-planned will in the first place.

The Administrator's Path: Navigating Probate Without a Will

When a loved one passes away without leaving a will, it creates a void that Texas law must fill. This situation is known as dying “intestate,” and it means the deceased left no instructions on who should manage their estate or how their property should be divided. As a result, the probate court has to step in and appoint an administrator to handle the complex process of settling their affairs.

Unlike an executor who is hand-picked by the deceased in their will, an administrator is chosen by the court based on a strict legal priority list. The Texas Estates Code establishes a clear pecking order for who has the right to serve.

The Legal Order of Priority

The court doesn't just pick an administrator out of thin air. Instead, it follows a specific sequence laid out in Texas Estates Code § 401.001. The order of preference is as follows:

- The surviving spouse.

- The principal beneficiary named in a will (this applies if the named executor can't or won't serve).

- Any other beneficiary named in a will.

- The next of kin, starting with the closest relatives.

This legal framework is designed to appoint someone with a genuine interest in the estate's proper management. But as you can imagine, it can also spark disputes if multiple heirs at the same level of kinship both want the job, leading to potential Probate Litigation.

The Heirship Proceeding and Administrator's Bond

Before an administrator can officially be appointed, the court first has to legally determine who the heirs are. This requires a formal court process called a Determination of Heirship. It’s a necessary step where the court identifies all legal heirs and their respective shares of the estate according to Texas intestacy laws. For a detailed look at this process, you can find more information in our article on exploring probate proceedings without a will.

On top of that, because the administrator wasn't personally chosen by the deceased, the court often requires them to purchase an administrator's bond. Think of it as an insurance policy that protects the heirs and creditors from potential mismanagement or fraud. The bond premium is paid from the estate's funds, adding another layer of cost to the process.

A Realistic Scenario: Siblings and a Dependent Administration

Let’s look at a common situation. Two adult siblings, Sarah and Mark, lose their father, who passed away without a will. Both are equally entitled under Texas law to serve as administrator, but they can't agree on who should do it, so they both petition the court.

The judge, sensing the potential for conflict, appoints Sarah but orders a dependent administration.

This means Sarah can’t do much on her own. She can't sell their father's house, pay a significant bill, or distribute any assets without first filing a formal application and getting the judge's written permission. Every single action requires more legal paperwork, court fees, and time, turning an already difficult situation into a lengthy and expensive ordeal. This scenario really drives home the difference between an executor and an administrator and shows how a simple lack of planning can deeply impact a family.

Comparing the Duties and Responsibilities

On the surface, executors and administrators look like they have the same job. They’re both fiduciaries, which is a legal term meaning they have a duty to act in the best interest of the estate and its beneficiaries. But that’s where the similarities end.

An executor follows the roadmap left behind in a will. An administrator, on the other hand, is guided by the rigid, one-size-fits-all instructions of Texas intestacy law. This single difference sends ripples through every task they perform, from paying bills to handing out inheritances.

While both are tasked with gathering assets, paying debts, and distributing what’s left, the how and why couldn't be more different. An executor is there to carry out the personal wishes of someone they likely knew. An administrator is there to execute the impersonal mandates of state law.

Authority and Decision-Making

The biggest divide between the two roles comes down to autonomy—especially here in Texas. A well-drafted will can grant an executor independent administration powers. This is a game-changer. It means they can handle most estate business, like selling a house or paying a creditor, without having to run to the court for permission every single time.

An administrator almost always operates under a dependent administration. Think of them as being on a short leash held by the probate court. Every meaningful decision—from selling the family car to paying the last hospital bill—requires filing a formal application and waiting for a judge to sign off on it. It’s a slow, cumbersome, and often expensive process.

Following the Estate's Blueprint

An executor’s mission is simple: honor the will. If the will says to sell a vintage Mustang and split the cash between two grandkids, that’s exactly what the executor does. Their path is laid out for them by the one person who knew the assets and heirs best.

An administrator has no such personal guide. They are stuck following the strict formula of Texas intestacy law, which decides who gets what based on a rigid family tree. This can lead to outcomes the deceased never would have wanted, like a distant cousin inheriting part of the estate while a lifelong unmarried partner gets nothing.

This difference has a real-world impact. Administrators, bogged down by court filings and formal heirship proceedings, often see the estate settlement timeline stretch to 18-24 months or more. The extra time and legal work can easily add $5,000 to $15,000 in professional fees. You can find more data on these administrative hurdles from the National Association of Estate Planners.

Core Duties: A Side-by-Side Look

Even though their guiding principles are worlds apart, many of their core tasks overlap. It’s crucial for anyone stepping into either role to understand these responsibilities. We dive deeper into this in our guide on the duties of a will executor.

Here’s a quick comparison of their fundamental jobs:

- Inventorying the Estate: Both must create a detailed list of every asset. An executor often gets a head start if the will mentions key properties. An administrator frequently has to start from square one, sometimes needing to hire investigators or appraisers to track down and value assets.

- Managing Creditor Claims: Both are responsible for notifying creditors and settling legitimate debts. An independent executor has the freedom to negotiate and pay these claims efficiently. A dependent administrator has to get the court’s permission before paying each and every bill.

- Asset Distribution: This is the final step. An executor gives assets to the beneficiaries specifically named in the will. An administrator gives assets to the legal heirs identified by the court in a formal heirship determination proceeding.

At the end of the day, a will that names an independent executor provides the clearest, most efficient, and most cost-effective path forward for your family.

The Real-World Impact on Your Family and Estate

Legal definitions are one thing, but the real-world difference between an executor and an administrator lands squarely on your family during an already difficult time. Having a will isn't just about paperwork; it's about handing your loved ones a roadmap for a faster, less expensive, and more peaceful probate process. When you name an executor, you’re giving them the gift of clarity.

Without a will, that clear path disappears. The court has to step in and appoint an administrator, which almost always triggers significant delays. Formal heirship proceedings must be held to legally identify the heirs, potential administrators need to be evaluated by the judge, and the court often requires a bond—adding yet another layer of time and expense.

Costs, Delays, and Family Harmony

The financial hit can be substantial. A dependent administration, which is common when there’s no will, means constant court oversight. Every major decision requires filing motions and attending hearings, racking up attorney fees and bond premiums that are all paid directly from the estate's funds. That means less is left for the people you wanted to inherit.

Just as important is the toll it takes on family relationships. Relatives are left to navigate a confusing legal maze with no clear leader chosen by the person who passed away, which can easily lead to tension and disputes over who should be in charge and how things should be handled.

Of course, the job doesn't stop at just settling debts and distributing property. Both executors and administrators must tackle the estate's financial picture, which requires a firm grasp of topics like understanding inheritance tax.

Ultimately, taking the time to create a will and name an executor is one of the most meaningful acts of care you can provide for your family. It minimizes their burden, protects their inheritance, and ensures your final wishes are honored efficiently and with dignity. It's so much more than a legal formality—it's a final gift of peace of mind.

Key Insight: Your Will is Your Voice

An executor is your chosen voice, empowered by your will to carry out your specific wishes efficiently. An administrator is the court's appointed voice, required to follow a generic legal script. The difference isn't just a title—it's about whether your personal instructions or state law will guide the final chapter of your affairs. A well-drafted will ensures your voice is the one that's heard.

Common Questions About Executors and Administrators

When you're navigating the probate process, it’s easy to get tangled up in the legal jargon. Families often have specific questions about their roles and what they can or can’t do. Let’s clear up some of the most common questions we hear from Texas families about executors and administrators.

Can an Executor or Administrator Get Paid in Texas?

Yes, absolutely. Both executors and administrators are entitled to be paid for their work, and frankly, they should be. It is a demanding job that carries significant legal responsibility.

The Texas Estates Code § 352.002 allows for “reasonable compensation,” which is typically calculated as a 5% commission on all the money the estate receives in cash and all the money it pays out in cash.

However, this is not a rigid rule. If an estate is unusually complex and requires extraordinary effort, the court can approve a higher fee. Conversely, if the estate is very simple and the 5% commission seems excessive for the work involved, the court has the authority to reduce it. The goal is always to provide fair payment for the time and responsibility required to settle an estate properly.

What Happens If the Named Executor Declines to Serve?

It happens more often than you’d think. Being an executor is a huge commitment, and sometimes the person named in the will just can't—or won't—take it on for personal or health reasons. If that’s the case, they can formally step aside by filing a document called a “renunciation” with the court.

If the will names a backup executor (which is always a smart move), that person can then step up. But if there’s no alternate, or if the alternate also says no, the court will appoint an administrator based on legal priority, just like it would if there was no will. This is exactly why it's so important to name at least one backup when creating your Wills & Trusts.

Must an Administrator Be a Family Member?

While Texas law gives first priority to the surviving spouse and then to the next of kin, an administrator doesn't have to be a relative.

Sometimes, there just isn't a suitable family member who is willing or able to do the job. Perhaps the heirs live out of state, are in the middle of a conflict, or simply feel overwhelmed by the responsibility. In these situations, the court can appoint another qualified individual or entity, such as a trusted family friend, a professional fiduciary, or even a bank’s trust department. The court's main priority is finding someone who can manage the estate competently and fairly for all interested parties, including potential Guardianship situations for minor heirs.

If you’re facing probate in Texas, our team can help guide you through every step — from filing to final distribution. Schedule your free consultation today.