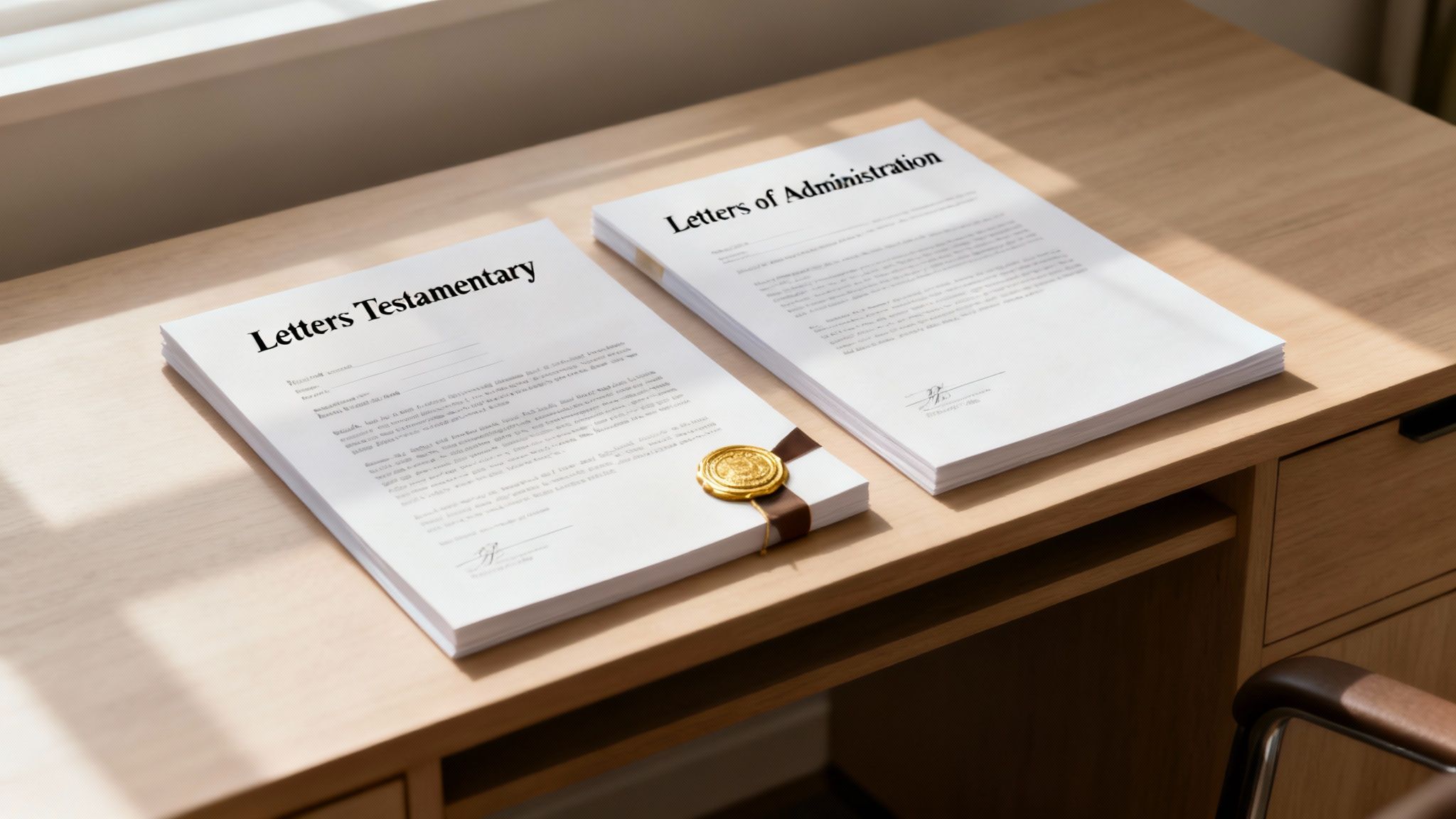

When a loved one passes away, the legal path forward hinges on a single, crucial question: did they leave a valid Will? Dealing with loss is difficult enough, and understanding the legal process shouldn't add to your burden. In Texas, the answer to that question determines whether the estate representative will need Letters Testamentary or Letters of Administration.

If a valid Will exists and names an executor, the court issues Letters Testamentary. If there's no Will, the court grants Letters of Administration to a court-appointed administrator. This distinction is the starting point for settling an estate and defines who receives the legal authority to manage your loved one's final affairs.

Beginning the Texas Probate Process

Losing a family member is overwhelming, and the legal complexities that follow can feel daunting. In Texas, the process of settling an estate—known as probate—begins with obtaining the correct legal document to act on your loved one's behalf. This document is your official key to handling their final affairs, from paying bills and accessing bank accounts to distributing property to the rightful heirs and beneficiaries.

The type of authority you need depends entirely on the presence of a valid Last Will and Testament. Grasping this difference is the first step toward gaining clarity and control during a difficult time. We're here to explain these concepts in plain English, so you can feel confident about the road ahead.

Comparing the Two Paths

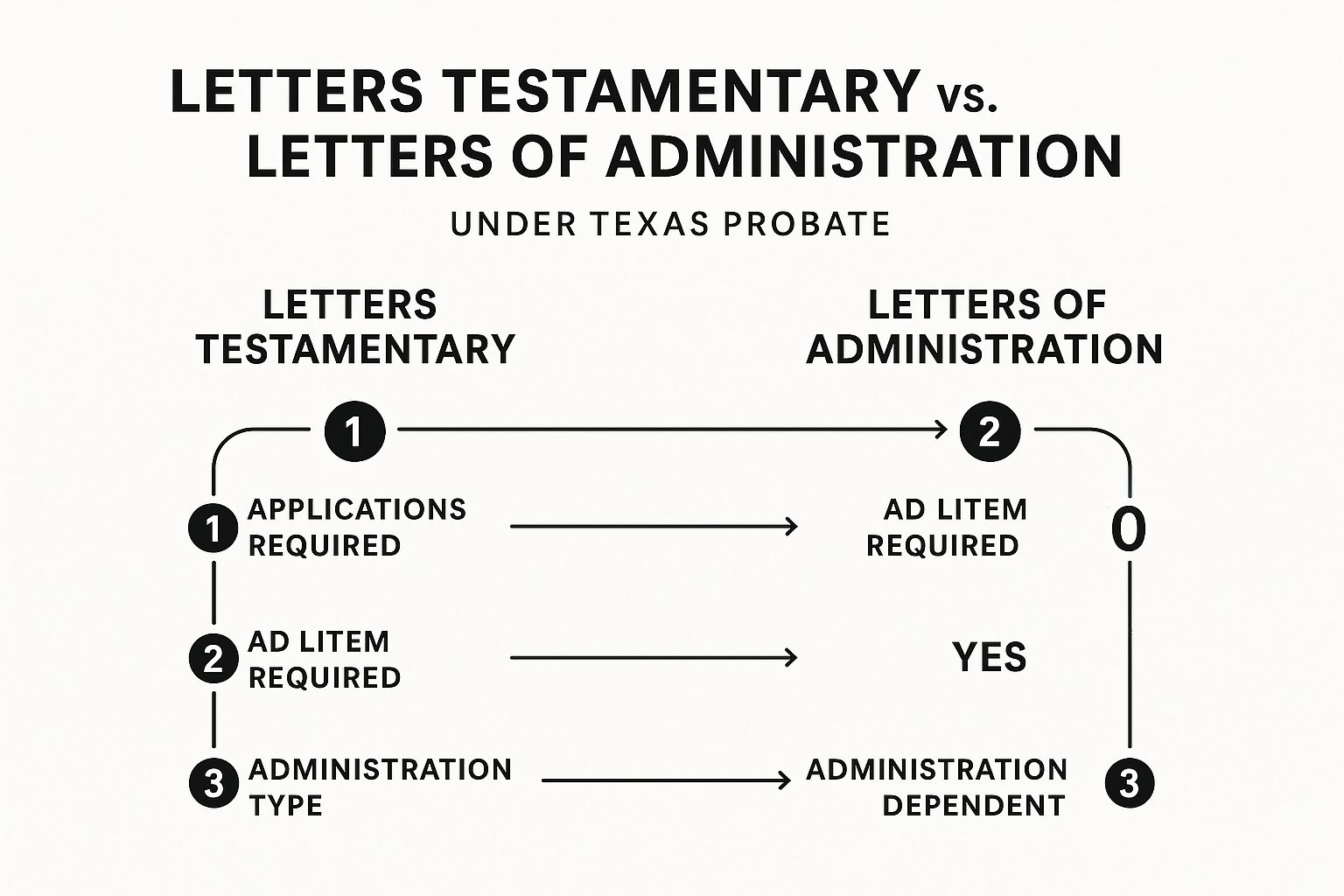

The table below breaks down the core differences between these two vital legal instruments. Think of it as a quick reference guide to help you understand the journey.

| Feature | Letters Testamentary | Letters of Administration |

|---|---|---|

| Prerequisite | A valid Will exists and is admitted to probate. | No valid Will exists (the person died "intestate"). |

| Appointed Person | Executor (named in the Will). | Administrator (appointed by the court). |

| Source of Authority | The deceased person's written wishes. | Texas state law (intestacy statutes). |

| Typical Process | Generally more direct and efficient. | Often more complex, requiring a formal heirship proceeding. |

Ultimately, both documents empower someone to legally manage an estate’s assets and debts. The journey to get them, however, follows two very different roads. For a deeper dive into the duties that come with this role, you can find valuable insights on navigating estate settlements and post-probate administration. Our goal here is to demystify these requirements and give you the reassurance you need to move forward.

When you begin the Texas Probate Process, one of the court’s first jobs is to grant someone the legal authority to manage the deceased's affairs. This authority comes in the form of a court order, but the name of that order depends entirely on whether a valid Will exists. While these two documents serve a similar purpose, their origins are completely different.

Letters Testamentary and Letters of Administration are both legal documents a probate court issues to allow someone to manage and settle an estate. The critical difference is that Letters Testamentary are granted when the deceased left a valid will, while Letters of Administration are issued when there's no will. You can learn more about the fundamental differences between these estate situations.

The Role of a Last Will and Testament

The presence of a Will is the dividing line in the letters testamentary vs letters of administration discussion.

Letters Testamentary are issued by the court when a person dies with a valid Will. This document is the court's official stamp of approval for the Executor—the person the deceased trusted and specifically named in their Will to carry out their final wishes. The Executor's power comes directly from the instructions left by the person who passed away, as validated by the court under the Texas Estates Code.

Letters of Administration are granted when a person dies intestate, the legal term for dying without a Will. Because the deceased didn't name an Executor, the court must appoint an Administrator to manage the estate. The Administrator isn't guided by the deceased's personal wishes but by the strict inheritance hierarchy laid out in Title 2 of the Texas Estates Code.

Key Insight: Think of a Will as a personalized set of instructions for your estate. Letters Testamentary empower your chosen representative to follow that unique map. Without a Will, the court hands over a generic, state-mandated map—Texas intestacy law—and appoints someone to follow it using Letters of Administration.

To put it simply, here’s how the key differences stack up:

Key Differences: Letters Testamentary vs Letters of Administration

| Attribute | Letters Testamentary | Letters of Administration |

|---|---|---|

| Triggering Event | Deceased left a valid Will. | Deceased died without a Will (intestate). |

| Person in Charge | Executor (named in the Will). | Administrator (appointed by the court). |

| Source of Authority | The deceased person's wishes outlined in the Will. | State law (Texas Estates Code). |

| Guidance | Follows the specific instructions in the Will. | Follows a statutory formula for who inherits. |

This distinction is crucial because it determines who is in control and what rules they must follow. An Executor's path is guided by the deceased person’s own directives, which often makes for a more straightforward process. An Administrator, however, must navigate a path dictated entirely by state law—a path that might not match what your loved one would have wanted.

Understanding this core difference is the first step in preparing for the journey ahead, whether you’re carrying out a loved one's final wishes or stepping up to manage an estate according to Texas law.

Comparing the Application Process in Texas

When a loved one passes away, the path to gaining legal authority over their estate splits in two, based entirely on whether they left a Will. The journey to get Letters Testamentary is typically more direct, while the process for Letters of Administration involves more legal steps designed to protect all potential heirs.

Knowing which procedural map you'll be following is key to setting realistic expectations for the timeline, costs, and paperwork involved. A valid Will acts as a clear set of instructions for the court, which almost always simplifies the entire affair.

Applying for Letters Testamentary When a Will Exists

If your loved one named you as the Executor in their Will, the application process is generally straightforward. Your main goal is to have the court legally recognize the Will as valid and officially install you in your role.

Here is a step-by-step guide on what to expect:

- File the Application: You, or your attorney, will file an "Application to Probate Will and for Issuance of Letters Testamentary" with the probate court in the county where the deceased lived. You can learn more about the specific documents you'll need when you file a petition for probate in Texas.

- Post Public Notice: A notice must be publicly posted at the courthouse for at least 10 days. This is a formality required by the Texas Estates Code to inform the public that a probate application has been filed.

- Attend a Court Hearing: After the waiting period, there’s a short, formal hearing. Here, you'll provide testimony to prove the Will is valid.

- Take the Oath: Once the judge validates the Will, you'll take an oath of office, officially accepting your duties as Executor. The court then issues the Letters Testamentary, giving you the authority to act.

This process is more efficient because the person who passed away already made the big decisions, especially the most important one: who they trusted to manage their estate.

The infographic below helps visualize the two different workflows for getting these crucial court orders.

As you can see from the flow chart, the absence of a Will forces extra, mandatory legal steps into the process—like appointing an attorney ad litem—that simply aren't needed when a valid Will is being probated.

Applying for Letters of Administration Without a Will

When there’s no Will, the process becomes more complicated. The court cannot simply appoint someone to manage the estate; it must first legally determine who the heirs are. This is a critical protective measure required by Texas law.

This path requires filing two connected applications:

- An Application for Determination of Heirship to legally identify everyone entitled to inherit under state law.

- An Application for Letters of Administration to ask the court to appoint an Administrator.

Key Insight: A significant difference here is the mandatory appointment of an attorney ad litem under the Texas Estates Code. This is an independent attorney the court appoints to represent the interests of any unknown or missing heirs, ensuring no one is wrongfully excluded. This step adds both time and expense to the probate case.

Only after the attorney ad litem has completed their investigation can a formal court hearing be held to legally establish who inherits. Once the judge signs an Order Determining Heirship, the court can finally move on to appointing an Administrator and issuing the Letters of Administration.

Who Can Serve as an Executor or Administrator

The court’s decision on who gets to manage an estate comes down to whether a valid Will exists. This answer dictates everything in the letters testamentary vs letters of administration discussion, including who is eligible to serve and how that person is chosen—a process guided by either personal choice or state law.

For Letters Testamentary, the choice is clear and personal. The person who passed away already made their selection by naming an Executor in their Will. This person has the first legal right to the job, and the court’s role is simply to honor that choice, assuming the individual is qualified.

But what happens if the named Executor cannot—or will not—take on the role? In that case, the court looks for a successor Executor also named in the Will. If no backup is listed, the beneficiaries might need to agree on a suitable replacement.

The Legal Hierarchy for Administrators

When there is no Will, the court cannot rely on the decedent's wishes. It must turn to the Texas Estates Code, which outlines a clear priority list for who can be appointed as the Administrator. This hierarchy is designed to be logical and fair, starting with the closest family members.

As outlined in Texas Estates Code § 304.001, the order of priority is generally:

- The surviving spouse.

- The principal beneficiary named in a Will (if one exists but the named Executor can't serve).

- Any other beneficiary named in the Will.

- The decedent's next of kin, starting with the closest relatives according to the laws of descent and distribution.

This legal framework means Letters of Administration require the court to appoint someone based on a statutory formula. This process can sometimes lead to extra court oversight or even disputes among heirs, known as Probate Litigation, which can prolong the probate timeline.

Key Insight: A Will is a direct instruction to the court about who you trust. Without it, the Texas Estates Code provides a default list, which may or may not align with who you would have chosen to handle your final affairs.

Regardless of the path, any person appointed must meet basic qualifications. In Texas, an Executor or Administrator must be of sound mind, at least 18 years old, and not have a felony conviction. For a deeper look, you can check out our guide on who can serve as an estate representative in Texas.

Understanding the Powers and Responsibilities of Each Role

While an Executor and an Administrator both have the profound responsibility of managing an estate, their freedom to act can be worlds apart. This difference in autonomy stems directly from the type of authority granted by letters testamentary vs letters of administration. At its heart is a critical Texas legal concept: independent versus dependent administration.

An Executor, armed with Letters Testamentary, almost always operates under an independent administration. This is because most well-drafted Texas Wills & Trusts specifically request it, granting the Executor power to handle most duties—paying debts, selling property, distributing assets—without seeking court permission for every action.

On the other hand, an Administrator holding Letters of Administration typically manages the estate through a dependent administration. This process is defined by constant court supervision. Nearly every significant action requires a judge's approval, a safeguard designed to protect heirs when there is no will to guide the process.

A Realistic Scenario: Selling the Family Home

Let's walk through a common example to illustrate the difference: the estate needs to sell the family home.

With Letters Testamentary (Independent Administration): The Executor, Sarah, whose mother named her in the Will, can list the house, accept an offer, and sign the closing documents on her own authority. The process moves at the speed of the real estate market, not the court's calendar, saving the estate time and money.

With Letters of Administration (Dependent Administration): The Administrator, John, appointed by the court for his brother's estate, has a much longer road. He must first file a formal application with the court seeking permission to sell. The court then schedules a hearing to decide if the sale is necessary and in the estate's best interest. Only after getting a signed court order can John begin the sales process, adding weeks or even months to the timeline.

This one example perfectly illustrates how an Executor's path is often far smoother and less stressful for the family involved.

Key Insight: Independent administration gives an Executor the flexibility to manage an estate efficiently. In contrast, dependent administration forces an Administrator to operate on the court's schedule, turning routine tasks into lengthy, permission-based procedures.

Ultimately, both roles are bound by a fiduciary duty to act in the estate's best interest. However, the authority granted by Letters Testamentary provides the flexibility needed to fulfill that duty far more effectively. To dig deeper into these crucial obligations, check out our guide on the Executor's roadmap and responsibilities under Texas law.

Key Takeaway: Why a Valid Will is So Important

The deep divide between obtaining Letters Testamentary and Letters of Administration all circles back to one simple truth: a valid Will is your final act of care for your family. It is the personal roadmap you leave behind, ensuring your wishes are honored without question during an already difficult time.

A Will does more than just say who gets what. It names a trusted person to wrap up your affairs, which dramatically simplifies the entire probate process, reduces costs, and provides peace of mind for those you leave behind.

Securing Your Family's Future

When you take the time to create a valid Will, you are shielding your family from needless emotional stress, extra costs, and frustrating delays. The path to Letters Testamentary is straightforward because you’ve already made the hard decisions. Without a Will, you leave those choices to Texas state law, forcing your family into the more tangled and expensive process of administration and heirship determination.

Key Insight: A Will transforms probate from a cold, court-mandated procedure into the fulfillment of your personal wishes. It’s the single most powerful tool for protecting your family from uncertainty and potential conflict after you’re gone. This is a key part of handling not just probate but also matters like Guardianship.

To avoid confusion and guarantee your wishes are carried out exactly as you intend, exploring comprehensive estate planning makes all the difference. The time you spend creating a Will today offers you invaluable peace of mind and gives your family essential protection for their future.

If you’re facing probate in Texas, our team can help guide you through every step — from filing to final distribution. Schedule your free consultation today.

Unpacking Common Probate Questions in Texas

When you're dealing with the loss of a loved one, the last thing you want is a mountain of confusing legal questions. Families navigating probate for the first time often have very practical concerns about how long it will take, what it will cost, and what to do when things don't go as planned. We're here to provide clear, plain-English answers.

How Long Does It Take to Get the Letters?

The timeline for getting court-issued Letters really depends on one key factor: is there a valid Will?

With a Will, the path to obtaining Letters Testamentary is usually much faster. Assuming the paperwork is filed correctly and no one contests the Will, you can often have the Letters in hand within four to eight weeks.

Things slow down considerably when there's no Will. Securing Letters of Administration typically takes three to six months, sometimes longer. This delay comes from a required legal step called an "heirship determination," where the court must appoint a separate attorney (an attorney ad litem) to independently verify the deceased’s legal heirs. Only after that process is complete can an administrator be appointed.

Is Getting Letters of Administration More Expensive?

In short, yes. The absence of a Will creates more work for the court and attorneys, which directly translates to higher costs for the estate.

The extra expenses come from a few key areas:

- More Court Filings: Instead of one application, the court requires two separate filings—one to determine the heirs and another to appoint an administrator.

- Attorney Ad Litem Fees: The estate is responsible for paying the fees of the court-appointed attorney tasked with finding and representing any unknown or missing heirs.

- Increased Legal Work: The whole process is simply more involved, requiring more of your attorney’s time to navigate the additional hearings and paperwork.

What if the Named Executor Cannot Serve?

It happens more often than you’d think. Someone named as executor in a Will may have passed away, become ill, or simply feel they aren't up to the task.

In this scenario, the first step is to check if the Will names a successor executor. If it does, that person is next in line to serve.

If there's no successor named, the beneficiaries can typically come to an agreement on who should manage the estate instead. When this happens, the court issues a special type of order called "Letters of Administration with Will Annexed." It's a hybrid solution that appoints an administrator to step in, but that person is still legally bound to follow the exact instructions laid out in the Will. This ensures your loved one's wishes are still honored, even if the original executor cannot serve.

If you’re facing probate in Texas, our team can help guide you through every step — from filing to final distribution. Schedule your free consultation today with the Law Office of Bryan Fagan, PLLC at https://txprobatelawyer.net.