When a loved one passes away without a will, the path forward can feel shrouded in fog. If you need to step in and manage their affairs in Texas, your goal is to be appointed as the estate's Administrator. The term Executor is a different role entirely—one reserved for when a will exists. Getting appointed as Administrator happens through a court process guided by state law, which sets out a clear pecking order for who is eligible to serve.

Navigating a Loss Without a Will in Texas

Losing a family member is deeply personal and challenging on its own. Discovering they didn't leave a will can add a layer of legal and financial stress you're not prepared for. Many Texas families find themselves in this exact spot, feeling lost about how to handle property, pay final bills, or simply honor their loved one's legacy. It's important to know that you are not alone and that Texas law provides a structured, step-by-step path forward.

When someone dies without a will, they are said to have died “intestate.” This is a plain-English term for a situation where the court must step in. Instead of an executor following the instructions in a will, the probate court appoints an Administrator to manage the estate.

The distribution of assets isn't left to guesswork or family arguments; it's determined by a legal framework called intestate succession, which is detailed in Title 2 of the Texas Estates Code.

Understanding Intestate Succession

Think of intestate succession as a default estate plan created by the state. Its main purpose is to ensure assets are transferred to the closest surviving relatives in a logical and fair manner. We help families with this every day as part of the Texas Probate Process.

Here’s what that typically means for families:

- The court will legally determine who the heirs are.

- An Administrator will be appointed to gather assets, pay off debts, and handle all the paperwork.

- Whatever property remains will be distributed according to the legal hierarchy.

It's a more common situation than you might think. A recent analysis revealed a staggering 34% rise in intestate estates over just two years in England and Wales, highlighting a worldwide need for families to understand this process. You can read more about the rise in intestate estates to see just how common this has become. This reality underscores why knowing how to become an administrator is so critical.

Before we go any further, let's clear up the terminology. People use "executor" and "administrator" interchangeably, but in the eyes of the court, they are completely different.

Understanding the Key Roles: Executor vs. Administrator

This table breaks down the crucial differences between the roles appointed with and without a will, so you can use the correct legal terms with confidence.

| Term | Governing Document | Source of Authority |

|---|---|---|

| Executor | Last Will and Testament | Named in the will and confirmed by the court |

| Administrator | Intestate Succession Laws | Appointed by the court according to state law |

Knowing these distinctions is key. It helps you understand what you're asking the court to do and shows you've done your homework.

Key Takeaway: When there's no will, you can't be an "executor." You must petition the court to be named the "Administrator." The court grants your authority through a document called Letters of Administration, which empowers you to manage all of the estate's affairs.

Understanding these key terms and the legal road map is the first real step toward gaining control and finding some peace of mind during a time of loss.

Who Can Serve as the Estate Administrator

When a loved one passes away without a will, one of the first questions that comes up is, "Who's in charge now?" Without a will to name an executor, the decision isn't a free-for-all for the family to debate. Instead, the Texas Estates Code, Section 304.001, lays out a clear legal pecking order for who can step up and be appointed as the estate administrator.

This legal hierarchy isn't random. It's designed to put the closest family members first, operating on the assumption that they are the most likely to have the family's best interests at heart. This structure gives families a predictable path forward and helps cut through some of the uncertainty that comes with an unexpected loss.

The Legal Order of Preference in Texas

Texas law sets a specific priority list for who gets the first shot at being appointed administrator. Knowing where you stand in this line is the first step to figuring out if you're eligible to manage the estate.

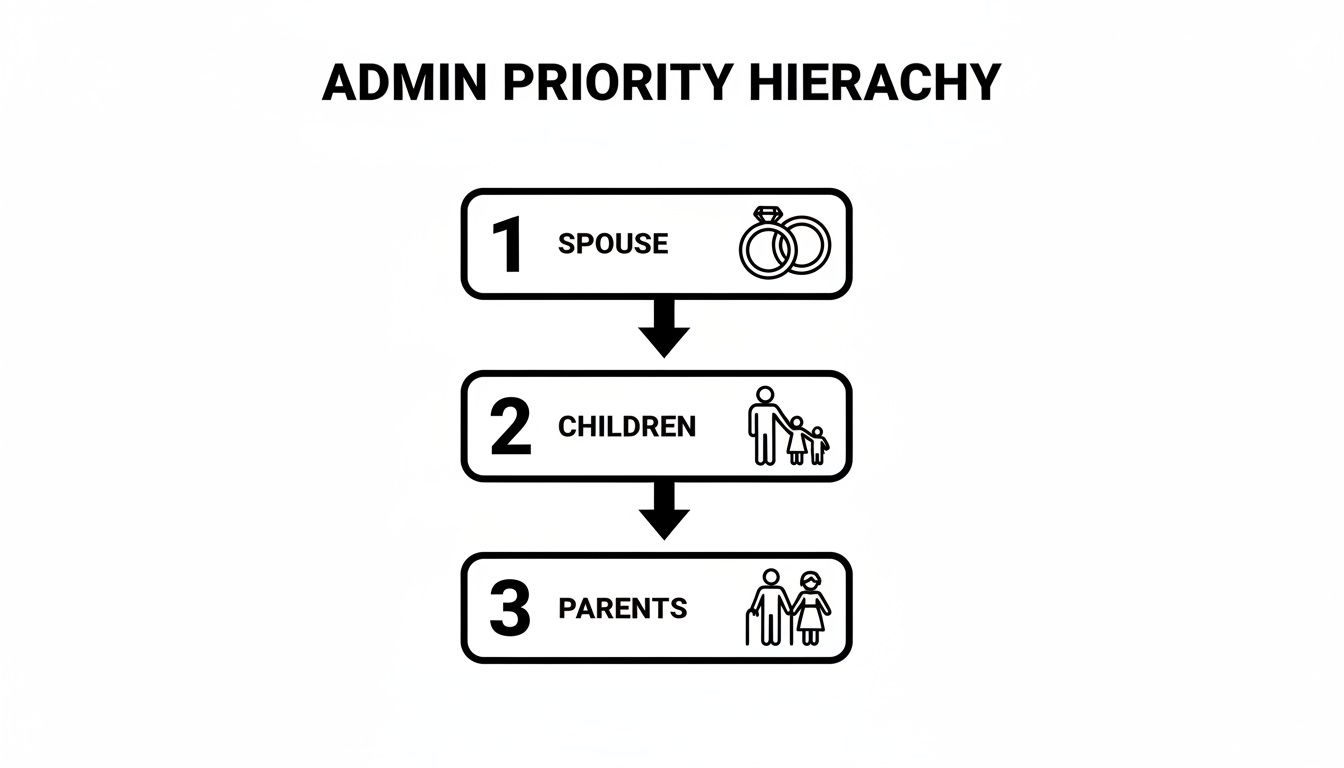

Here’s how the priority breaks down:

- The Surviving Spouse: The deceased person's spouse is at the top of the list and has the first right to apply.

- The Principal Devisee or Legatee: This usually only comes into play if there's a will but no named executor. Since we're talking about intestate estates (no will), this one typically doesn't apply.

- Any Devisee or Legatee: Again, this is for situations involving a will.

- The Next of Kin: This is the key category for most intestate estates. "Next of kin" refers to the closest living relatives according to Texas's succession laws. This generally starts with the deceased's children, then their parents, and then their siblings.

- A Creditor of the Deceased: If no family members are willing or able to take on the role, a person or company that the deceased owed money to can apply to serve.

- Any Other Person of Good Character: In the rare case that no one else steps forward, the court can appoint any suitable person who lives in the county.

This structured priority means that if you're the surviving spouse, you have the primary right to serve. If there's no spouse, the deceased’s children would all have equal standing to apply. We have an in-depth article that further explores who is eligible to serve as a personal representative in Texas.

Key Insight: The court's main goal is to appoint someone qualified and trustworthy to protect the estate's assets for both heirs and creditors. The legal priority list is just the starting point; the applicant also has to meet some basic qualifications.

Essential Qualifications to Serve as Administrator

Just being high on the priority list isn't enough. An applicant must also be legally qualified. Under Texas law, a person is disqualified from serving as an administrator if they are:

- A minor (under 18 years old)

- An incapacitated person (judged by the court to be of unsound mind), which may involve a Guardianship proceeding.

- A convicted felon (unless their civil rights have been restored)

- A person the court finds "unsuitable" for any reason

That "unsuitable" category gives the judge a lot of discretion. For example, someone with a history of fraud, a major conflict of interest with the estate, or a track record of financial mismanagement could easily be deemed unsuitable by the court.

A Real-World Scenario: Sibling Cooperation

Let's look at a realistic scenario. Maria, a widow, passed away without a will, leaving behind two adult children, Alex and Brenda. As "next of kin," both Alex and Brenda have equal priority to serve as administrator. Alex lives out of state, but Brenda lives right there in Houston, near their mother's home.

After talking it over, they agree that Brenda is in a much better position to handle the day-to-day tasks—securing the house, dealing with local banks, and meeting with the lawyer. Alex can then formally waive his right to serve, which lets Brenda apply without any family conflict. This kind of cooperative approach is often the smoothest path forward and avoids potential Probate Litigation.

Sadly, dying without a will is far from rare. National data shows that a huge number of Americans pass away without a will in place. Research using data from the Health and Retirement Study found that nearly 40% of people died intestate over a 17-year period. Another study showed about 30% of Americans aged 70 and older still don't have a will. You can discover more insights about these estate planning trends and see why understanding this process is so critical for so many families.

The Practical Steps for Court Appointment

Once you've figured out who is eligible and willing to step up as the administrator, it's time to formally petition the Texas probate court. This isn't a casual process; it’s a structured and methodical series of steps designed to make sure every legal box is checked. Knowing what's coming can turn a potentially overwhelming task into a manageable one.

The goal here is simple: present a clear case to the judge, showing you're the right person to settle the estate according to Texas law. This journey begins with preparing and filing two critical legal documents.

Filing the Initial Applications

The court process officially kicks off when your attorney files two key petitions on your behalf. These documents lay out all the essential facts for the court about the deceased, their family, and their estate.

Application for Letters of Administration: This is your formal request to be appointed as the estate's administrator. It must include specifics like the deceased's name, date of death, county of residence, and a clear statement that they died without a will. You’ll also need to state your relationship to the deceased and confirm you are legally eligible to serve.

Application to Determine Heirship: Since there’s no will to name beneficiaries, the court has to legally establish who the heirs are. This application lists all known family members—spouse, children, parents, siblings—and details their relationship to the person who passed away. This is a crucial step to ensure the right people inherit the estate assets as Texas law dictates.

Your first major task is gathering all the information needed for these applications. This means tracking down death certificates, marriage licenses, birth certificates for all children, and the names and addresses of all known relatives. Accuracy is everything here, as any mistakes can cause serious delays.

For a more detailed look at this initial filing stage, check out our guide on how to file for probate in Texas without a will.

The Role of the Attorney Ad Litem

After the heirship application is filed, the court will appoint an attorney ad litem. This is a plain-English term for an independent attorney whose job is to represent the interests of any unknown or missing heirs. Think of them as a court-appointed investigator, dedicated to protecting people who might have a claim to the estate but don't even know these proceedings are happening.

The attorney ad litem will conduct their own investigation. This usually involves interviewing you and other family members, reviewing the documents you filed, and searching public records to confirm no potential heirs have been overlooked. Their diligence is what makes the final court order legally sound and protects everyone's rights.

Key Insight: The attorney ad litem works for the court, not for you. Their role is to provide an objective report to the judge, confirming that all potential heirs have been found and properly notified. Their fee is an administrative expense paid directly from the estate's assets.

Public Notice and Waiting Period

Texas law requires that the public be notified about the probate application. This is done through a process called posting citation. Essentially, the county clerk posts a notice at the courthouse (or online) stating that an application has been filed for the estate.

This notice has to stay posted for at least ten days. This waiting period gives creditors or other interested parties a chance to see the filing and present any claims or objections they might have. It's a standard, non-negotiable part of the timeline.

To help visualize the priority order for who can serve, this infographic shows the legal hierarchy established by Texas law.

This visual hierarchy reinforces the legal preference outlined in the Texas Estates Code, showing how the court prioritizes the closest family members for the administrator role.

The Court Hearing

After the notice period ends and the attorney ad litem has completed their report, the court will schedule a hearing. This is your chance to formally present your case to the judge. While the idea of a court hearing might sound intimidating, it's typically a brief and straightforward proceeding, especially when no one is contesting it.

During the hearing, your attorney will guide you through your testimony. The judge will ask you a series of questions under oath to confirm the facts presented in your applications.

You can expect questions like:

- Was the deceased a resident of this county?

- Did the deceased leave a will?

- Are you aware of any debts owed by the estate?

- Are you qualified to serve as administrator?

You will also need to bring a neutral witness—someone who knew the deceased but is not an heir—to provide brief testimony confirming some of the family history. This helps corroborate the information in the heirship application. If everything is in order, the judge will sign an Order Determining Heirship and an order appointing you as administrator.

Securing Your Administrator's Bond and Oath

When the judge finally signs the order approving your application, it’s easy to feel like you’ve crossed the finish line. You’ve cleared a major hurdle, but there are two critical steps left before the court will hand over your Letters of Administration—the document that gives you official authority to manage the estate.

These final steps—securing a bond and taking an oath—are essential legal formalities designed to protect the estate’s assets and ensure you fully grasp the weight of your new responsibilities.

Understanding the Administrator's Bond

The court's number one job is to protect the estate's assets for the rightful heirs and any creditors. To do this, Texas law almost always requires a newly appointed administrator to post a bond.

In plain English, an administrator's bond is an insurance policy for the estate. It’s a financial guarantee you purchase from a surety company. This bond protects the heirs and creditors from any potential financial damage caused by mistakes, negligence, or even intentional misconduct on your part as you manage the estate.

The judge sets the bond amount, which is usually equal to the estimated value of the estate's personal property—things like cash, stocks, and vehicles. It doesn't include real estate. The cost of the bond, called the premium, is paid from the estate's funds, not out of your own pocket.

Key Insight: A bond isn't a reflection of the court's trust in you personally. It's a standard legal safeguard required in most dependent administrations to guarantee that if assets are mishandled, the estate can be made whole.

How to Potentially Waive the Bond Requirement

Posting a bond can be a hefty expense, especially for larger estates. The good news is that Texas law provides a way to sidestep this cost under the right circumstances. A court may agree to waive the bond requirement if all of the legally determined heirs agree to it in writing.

This is a powerful option for families who have complete trust in the person appointed as administrator. Getting a signed, notarized waiver from every single heir and filing it with the court can save the estate thousands of dollars.

Realistic Scenario: The Garcia Family

Let's picture the Garcia siblings after their father's heirship proceeding. The court agrees to appoint the oldest son, David, as administrator. The estate's personal property is valued at around $150,000, which would mean a pretty expensive bond.

Because all three siblings trust David implicitly, their attorney drafts a "Waiver of Bond" document. Each sibling signs it in front of a notary, and the attorney files it with the court. Seeing this unanimous agreement, the judge waives the bond requirement. This simple step preserves more of the estate's assets for the heirs. To get a more detailed look at this, you can learn more about when a bond is required in Texas probate.

Taking the Oath of Administration

The last box you need to check is taking the Oath of Administration. This isn’t just paperwork; it's a formal, sworn promise you make to the court.

By taking this oath, you are legally affirming that you will faithfully and diligently perform all of your duties as an administrator according to the law.

The oath is typically a simple, one-page document you sign at the county clerk's office. Once you have filed your bond (or the signed waiver) and your oath, the clerk will finally issue your Letters of Administration. This document is your official proof of authority—the key that lets you access bank accounts, talk to creditors, and manage all the estate's assets.

Your Duties After Receiving Letters of Administration

Getting those official Letters of Administration from the court is a huge moment. This single document is your golden ticket—the legal proof you need to act on behalf of the estate. But while it signals the end of your appointment journey, it’s the true beginning of your work as the administrator.

Your role officially shifts from applicant to fiduciary. That’s a legal term with a lot of weight behind it. It means you are now bound by law and ethics to act in the absolute best interest of the estate and its heirs. This is a responsibility that can be prepared for by creating thorough Wills & Trusts.

The court and the family are putting immense trust in you. From here on out, meticulous organization and crystal-clear communication are your best friends. They'll keep you on the right side of the law and help you navigate the responsibilities ahead.

Marshalling and Inventorying Estate Assets

Your first major assignment is to track down and take control of everything the deceased owned. In legal speak, this is called “marshalling the assets.” Think of yourself as a financial detective. You’ll be digging into bank accounts, locating property deeds, finding vehicle titles, and securing personal belongings.

Once you have a handle on everything, you need to report it all to the court in a formal document called the Inventory, Appraisement, and List of Claims. The Texas Estates Code is very clear on this: you must file it within 90 days of your appointment.

This inventory must include:

- A complete list of all real estate located in Texas.

- A detailed list of all personal property, no matter where it is.

- A list of any claims the estate has against others (for example, money someone owed to the deceased).

You can’t just jot things down. Each item needs a clear description and its fair market value on the date the person passed away. This isn’t just busywork; it's the official accounting that sets the foundation for the entire administration. For things like personal property that might be sold, knowing how to price estate sale items can be incredibly helpful for getting the valuations right.

Key Insight: Don't mess around with the inventory. Accuracy is everything. A sloppy or incomplete inventory can cause massive delays, spark fights among heirs, and even leave you personally liable for mistakes. Get this part right.

Notifying Creditors and Handling Debts

With the inventory filed, your attention turns to the other side of the ledger: the estate’s debts. Texas law requires you to publish a notice in a local newspaper. This formally announces that the estate is open and starts the clock for creditors to come forward and make a claim.

You also have to send a direct, formal notice by certified mail to any secured creditors you know about, like the bank holding the mortgage on the house. Your job is to scrutinize every claim that comes in. You'll use estate funds to pay the legitimate debts before a single dollar goes to the heirs. If a claim seems bogus, you have the right to formally reject it and make them prove it.

Managing, Distributing, and Closing the Estate

While all this is happening, you're also the manager of the estate's property. This could mean paying the mortgage to prevent foreclosure, keeping up with property maintenance, managing investment accounts, or just making sure valuable heirlooms are stored safely. You’ll also need to file the deceased's final income tax return and possibly an income tax return for the estate itself.

Only when every last asset has been collected, the inventory approved, all legitimate debts and taxes paid, and all administrative costs covered can you finally start distributing what's left to the heirs. The division of property must follow the court's Order Determining Heirship down to the letter.

Once everyone has received their share, you’ll file a final accounting with the court, ask to be officially released from your duties, and formally close the estate. A word of advice from experience: keep the heirs in the loop throughout this whole process. A simple update can prevent a world of misunderstanding and build the trust you need to get the job done smoothly.

Answering Your Top Questions About Texas Estate Administration

When you’re navigating the administration process without a will, it feels like a new question pops up at every turn. The legal path can seem confusing, but getting clear answers to the most common concerns can provide a sense of control and direction. Let's tackle some of the most frequent questions we hear from Texas families in this exact situation.

How Long Does It Take to Get Letters of Administration?

This is usually the first thing people ask, and for good reason—you can't do anything without them. While every case has its own rhythm, you can generally expect it to take anywhere from two to six months from the day you file the first application to the day you have Letters of Administration in hand.

What causes the timeline to stretch? A few things can slow it down:

- The Court's Schedule: Some probate courts are simply busier than others. The judge's docket plays a huge role.

- Finding the Heirs: If heirs are scattered across the country (or the globe) or are just hard to track down, the notification process and getting waivers signed can add weeks or months.

- The Complexity of the Estate: A straightforward estate with a house, a bank account, and clear heirs will move much faster than one with business interests, complex investments, or disputed property.

- Family Harmony (or Lack Thereof): When all the heirs are on the same page, things can move surprisingly fast. But if there’s a disagreement, everything grinds to a halt until the dispute is resolved.

The single best way to keep things moving is to work with an experienced probate attorney who knows how to file everything correctly the first time and anticipate potential roadblocks.

What Happens If Heirs Can’t Agree on Who Should Be the Administrator?

It’s a scenario we see all the time, especially among siblings who all have an equal legal right to serve. When the family can't come to an agreement, the decision ultimately rests with the probate judge.

The court will set a hearing where anyone who wants to be administrator can make their case. The judge will listen to all sides, but their primary goal isn't to pick a favorite—it's to protect the estate's best interests. They will appoint the person they believe is most qualified to manage the estate’s business responsibly, fairly, and without bias. This is exactly the kind of situation where having a skilled attorney to advocate for you can make all the difference.

Can We Just Use a Small Estate Affidavit Instead?

A Small Estate Affidavit, or SEA, is a fantastic shortcut to formal administration, but it has very narrow and strict rules. It's only a viable option if the person who passed away:

- Did not have a will.

- Left behind an estate worth $75,000 or less (this amount does not include their homestead).

- Had more assets than debts (not counting the mortgage or other debts secured by the homestead).

The biggest limitation is that an SEA generally can't be used to transfer title to real estate, other than the homestead. It's really designed for simple, low-value estates. If the situation is any more complex, a formal Dependent or Independent Administration will be necessary.

Key Takeaway: A Small Estate Affidavit can be a lifesaver in the right circumstances, but it’s not a one-size-fits-all fix. Trying to use it incorrectly can cause major legal headaches down the road, so it's critical to confirm with an attorney that the estate actually qualifies.

What Does It Typically Cost to Become an Administrator?

One of the first things to know is that these costs are paid from the estate's assets, not out of your own pocket. The main expenses you'll see include:

- Court Filing Fees: This is the fee to get the process started, usually a few hundred dollars.

- Attorney Ad Litem Fees: The court appoints this attorney to find unknown heirs. Their fee often runs between $500 to $1,500, sometimes more depending on how much digging they have to do.

- Administrator's Bond Premium: This is like an insurance policy for the estate. The cost is a percentage of the bond's value, but this entire expense can often be waived if all heirs agree.

- Your Probate Attorney's Fees: This is the cost for professional legal guidance to make sure every step is handled correctly, preventing expensive mistakes and keeping the process on track.

If you’re facing probate in Texas, our team can help guide you through every step — from filing to final distribution. Schedule your free consultation today.